Lt Cdr Cumming Report

Note: from our President John Carroll

I have highlighted those parts of this report which, to the best of my knowledge and belief, no one has ever seen before. It also highlights the inequity of the Nominal Roll, where Army personnel, who served pre the official dates of involvement, have their service recognised, whereas the RAN member is not recorded on this Roll or acknowledged anywhere else at all. Another fault of the Senior Service also being the Silent Service. I can only hope things have improved over the years. I have left that part of Chapter Three of Out of Sight, Out of Mind in so that the new portion can be read in context with that part of the Chapter.

Early Days - RAN - South Vietnam War Zone

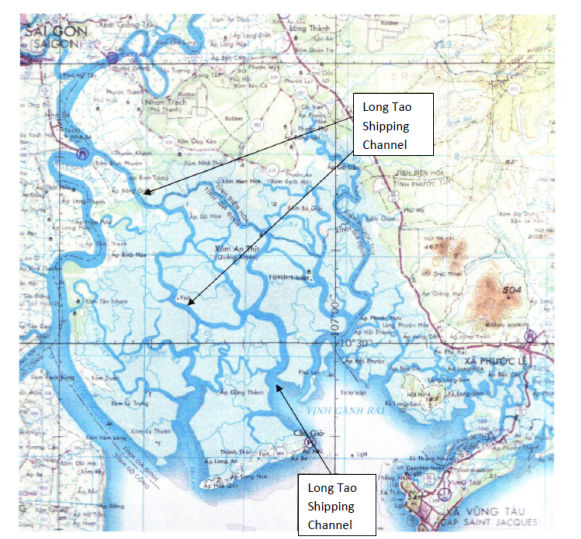

It was via a narrow twisting channel through dense mangrove swamp

that ships passed from the South China Sea to the piers and moorings

of Saigon. Mines in the

channel could put an end to that traffic.

The area through which the channel made its way was known as the

Rung Sat Special Zone (RSSZ), a dangerous four hundred square mile

expanse of mangrove swamps and mudflats.

[i]

Long Tao Shipping Channel – Rung Sat Special Zone

[ii]

As an integral part of Australia’s policy of forward defence, the

RAN was fully involved. Effectively, not only was the Navy’s

presence in Vietnam much more significant from a defence perspective

than is often assumed, it also began at a much earlier stage than

the other two services, and several years before the first thirty

Australian Army advisers arrived in Vietnam in August 1962,

purportedly in non-combatant roles.[iii]

Historical theses of the Australian military deployment in

Vietnam rarely, if ever, mention that RAN ships visited South

Vietnam in the mid 1950’s and early 1960’s. While serving with the

FESR based in Singapore, during the Malayan Emergency, the

destroyers Anzac and

Tobruk both made separate

visits to the then South Vietnam capital city port of Saigon in

October 1956, and December 1957 respectively. Visits then followed

to the ports of Nha Trang and Saigon, undertaken by

Vampire and

Quickmatch on 25 January

1962, ostensibly to mark the occasion of Australia Day, followed by

similar visits to Saigon by the two frigates,

Quiberon and

Queenborough on 31

January 1963. These visits,

per se, were officially classified as diplomatic port visits by

the Australian Government, with their sole purpose being hailed as

demonstrating Australian support for South Vietnam, which had been

embroiled in armed conflict with a range of anti-government forces

since its inception in early 1955.[iv]

Unofficially, Vampire and

Quickmatch were also

given the covert task of accurately assessing the viability of a

ship the size of Sydney

being able to access the port of Saigon, for the troop

transportation and logistical support roles in which she would

subsequently be employed.

The berthing facilities had been used by at least two light

French aircraft carriers and several American auxiliary aircraft

carriers in the past; and the port was reportedly readily accessible

to ships drawing 9.3 metres (30 feet) and up to 180 metres (590

feet) in length.[v]

Sydney was known to

exceed these dimensions by over forty feet (12 metres) at the load

water line (LWL) and by more than 100 feet (30 metres) in length

overall (LOA). Both factors would have affected

Sydney’s

ability to manoeuvre in the restrictive confines of the narrow,

twisting Long Tao shipping channel.

Despite the diplomatic classification for these visits, by 1962 it

was quite evident that both

Vampire and Quickmatch

were exposed to some considerable risk when they entered the

Long Tao shipping channel, and made their way up the Saigon River

system. Captain Anthony Synott, then the Commanding Officer of

Vampire, later wrote

that:

In January 1962, HMAS Vampire

under my command visited Saigon in company with HMAS

Quickmatch. There is no

doubt that Vietnam was on a war footing at the time and we were

required to take all necessary precautions.[vi]

Commander Peter Doyle, Commanding Officer of the accompanying

frigate, HMAS Quickmatch,

confirmed the circumstances of the visit, and wrote in some detail

of the task he was delegated to perform by Synott:

In essence, the task delegated to me by the Commanding Officer of

HMAS Vampire was to

report on the feasibility of HMAS

Sydney being able to

berth in Saigon. In preparation of my report I used:

* French charts of the Saigon River.

* Discreet discussions with local pilots – a small US carrier had

berthed in the Saigon River probably

near the refinery oil storage area about a year before.

* Discussions with Colonel Hopton the Australian Defence Attaché.

* My observations of the river passage both inward and outward.

* From recollection, I believe my report concluded that from a

purely pilotage and ship handling point of

view – at least as far as the oil storage refinery, HMAS

Sydney could navigate the

Saigon River. However, the possibilities of mine warfare, swimmer

attack and shellfire from the countryside made the risks

unacceptable.[vii]

This element of risk and danger applied not just to the ships

involved, but also to the officers and sailors who ventured ashore

on official duty. The observations of Lt. Cdr. Peter M Cumming show

a first-hand perspective.[viii]

Cumming visited South Vietnam during the period, 14 December 1962 to

14 January 1963, as an RAN observer. At the time, he was the

Executive Officer of HMAS

Quiberon, which was scheduled to visit South Vietnam in late

January 1963.

Following official briefings and introductions, Cumming met with

Captain J B Drachnik, USN, head of Navy section, Military Assistance

Advisory Group (MAAG), and formulated a program to cover the period

of his stay, until planned amphibious landings against enemy forces

in the south commenced early in January 1963. As Cumming noted:

As the plans for the landings had reached draft form there was

nothing I could do to assist, and I therefore decided to use the

rest of December familiarising myself with the proposed operation,

visiting as much of SVN as possible, assisting the Australian

Defence Attaché (ADA) with arrangements for the RAN visit in

January, and generally observing activities naval, in and around

Saigon.

[ix]

On Tuesday 18 December, Cumming met with Lt. Cdr. Liem at

the Ministry of Defence, followed by Captain Ho Tan Quyen, Commander

of the VNN at Naval Headquarters, who briefed both Colonel Hopton

and Cumming on the forthcoming Ca Mau landings. On the following

Saturday, he accompanied Hopton to the graduation ceremony at the Da

Lat Military Academy. On Boxing Day, he was shown over the Saigon

shipyard and inspected the new command junks being constructed

there.[x]

The next day, Cumming flew to Da Nang via Pleiku. He was briefed on

activities in the north at HQ One Corps by VNN and MAAG

representatives there, and met with Lt. Trang, the district naval

commander. He then met with Captain P Young and the men of the USN

Seal Team stationed at Da Nang. Next day, in company with the local

USN advisor, Lt. Ryan, Cumming visited the resident US Marine

helicopter flight and discussed the area with their Intelligence

Officer (IO). That afternoon, he was taken to the naval base on an

island at the entrance to Tourane Harbour, and observed the training

of the Biet Hai (Sea Force Commandos). From there, Cumming returned

by air to Saigon.[xi]

At 0700 on New Year’s Day 1963, Cumming joined VNN LST 500 at the

Saigon shipyard, slipping from alongside at 0800 to commence the

WAVBROLO campaign. Also onboard were Captain Quyen, Captain Drachnik,

Colonel Moody USMC, and other USN advisors, plus VNN staff officers

and communications personnel. All told, a total of 700 marines and

120 naval personnel were embarked, with a full complement of stores,

filled sandbags, fresh water, and assault boats. Passage down river

was interesting but uneventful, anchoring at Vung Tau at 1300,

approximately 1.5 miles north of Banc de Phare, Can Gio, where

practice landings of marines at Can Gio were undertaken, using one

command junk, five junks and the LST’s four Landing Craft.[xii]

At 1900, LST 500, in company with VNN LSM’s 403 and 328, proceeded

via the western side of Puolo Condore (Con Son) Island to an

anchorage off Ca Mau Point, which was reached at 2200 on Wednesday 2

January. Here,

the force was joined by two LCU’s and 15 junks from Phu Quoc Island.

The extensive shoaling off Ca Mau Point forced the flotilla to

anchor some four miles offshore, with choppy seas making boat-work

extremely difficult.[xiii]

The landing of the southern battalion at 0800 the next day

went as planned. Air support was provided and an underwater

demolition team had cleared and reconnoitred the beaches before the

landings, which were not opposed.

As Cumming noted ‘All villagers had disappeared from Xom Mui

and Xom Rach Tau, leaving only the usual booby traps, grenades and

stakes behind. All river mouths in the area were heavily barricaded

with stakes.’[xiv]

Regarding the landings, Cumming also wrote:

All landing on the 3rd went well, the only casualties

being one KIA and 2 WIA in the northern landings due to a land mine.

Immediately the marines had been landed, which required two lifts by

junk and LCVP and final approaches by 15 ft. SSB’s with outboard

engines, the job of offloading stores to the beaches commenced and

continued all the next day. All fresh water had to be supplied by

the ship.

PM 4th, I landed at Xom Mui with Captain Drachnik and was

grateful for borrowed khaki clothing and weapons. The village is up

a tidal creek, built on stilts, and surrounded by nauseous mangrove

swamps. … I returned to

the LST by SSB and junk that evening. Captain Quyen brought Lt.

General Cao, Commander IV Corps, and the civilian provincial

governor aboard for the night.

Fifth and 6th I spent onboard, where Captain Quyen had

his command post until a site could be found ashore. On the 6th

an LCM was attacked going upstream in the northern sector by Viet

Cong (VC) guerrillas using an electrically detonated mine. The LCM

was missed, but was ambushed when it withdrew and two sailors were

wounded. Positive results up to that date were occupation of initial

objectives, clearing traps and defences, and the capture of some 50

suspect civilians. Quite a large amount of VC equipment was also

taken.

I joined LSM 403 on the evening of the 6th, and we sailed

at midnight for the northern area. We arrived off the Bo De river

mouth at 0800/7th, and on being joined by LCU 539 and

533, we entered the river at 1100. All guns were manned, as the VC

is active on both banks, which are only 150 yards apart. We anchored

inside the entrance and sent civil guard platoons ahead to join

Rangers clearing VC from the village at the entrance to Rach Duong

Keo. At 1230, we

beached near the village where VC elements were being driven away

with small arms fire, but with no discernible casualties, as we came

in.

At 0730 Tuesday 8th, I left LSM 403, landed my gear at

Nam Can, and left by LCM to visit the area of the northern landings.

We arrived at the village of Xom Ong Trang at 1300, the passage was

unopposed. VC controlled villages on the southern shore were

apparently deserted. However, the LCM had been fired on the day

before, and had replied with tracer, burning down a long house. We

stopped all craft on the river while on passage, searched them and

interrogated their occupants.

I managed to hitch a ride on an ARVN H34 helicopter and left Nam Can

at 1230 Wednesday 9th. The alternative was to wait for a

charcoal convoy leaving on the 10th and taking three days

to fight its way up the canal to Ca Mau, with safe and timely

arrival NOT guaranteed. I decided to take my chances with the

Vietnamese chopper pilot instead.[xv]

Cumming returned to Quiberon

via Saigon and Singapore, and remained in the ship until 21

February. It appears that Cumming’s service in Vietnam has not been

acknowledged in any official documentation. His name and service

details do not appear on the Vietnam Veterans Nominal Roll, as do

153 of the 220 members of the ship’s company of HMAS

Quiberon. Whereas Colonel

Hopton, the Australian Defence Attaché who accompanied Cumming for

the initial part of his visit, has had his name and service details

recorded on this Roll.

[xvi]

In late January 1963, the frigates

Queenborough and

Quiberon were deployed to

the South Vietnam ports of Nha Trang and Saigon from their duties

elsewhere in the Southeast Asian region.[xvii]

While at Nha Trang, a group of twenty sailors from each ship

landed to visit the Vietnamese Army’s Ranger training centre at Duc

My - approximately 50 kilometres from Nha Trang. The Commanding

Officer of Quiberon,

Commander Vernon Parker noted in his ROP for January that: ‘It was

obligatory for all personnel to be armed as ambushes by the Viet

Cong are by no means uncommon in the area.’[xviii]

Lieutenant Commander Frank Woods Commanding Officer of

Queenborough, later

confirmed Parker’s observations, and noting in his ROP that:

During the four-hour passage up the Saigon River an armed patrol

craft and spotter aircraft to detect signs of threat from the river

bank were provided. After berthing at Saigon 24-hour security

measures were provided to both ships by South Vietnamese

authorities.[xix]

When Vampire and

Quickmatch made their

‘Australia Day’ visit to the South Vietnam port of Saigon on 25

January1962, they entered what could only be termed an active ‘war

zone’. From an official government point of view, however, this was

not the case. Australia’s official involvement is recorded as

beginning upon the arrival of ‘Colonel F P Serong in Saigon on 31

July 1962, and that this date marks Australia’s entry into the

Vietnam War.’

[xx] But even official versions

of events can sometimes be incorrect. As Serong has noted in some

detail:

My first arrival in Vietnam was mid-April 1962. At that time, the

war was fully ongoing. Passage up and down the river, to and from

Saigon by warships was a tactical operation conducted as such – an

operation of war. This had been the long ongoing status at that

date, and, from my later knowledge, for many months before.

[xxi]

Sound judgement also dictates that RAN ships entering a restricted

waterway - in what could best be described as an area of strategic

importance and likely to be subject to an unprovoked attack at any

time - would need to adopt proven defensive measures commensurate

with the conditions then faced. The fact that Synott had ordered

such defensive measures be adopted aboard

Vampire and

Quickmatch for the

four-hour transit of the Long Tao shipping channel, both going

upstream and when coming back down, indicates that a real threat of

risk and danger did exist.[xxii]

That this state of affairs was apparently ongoing is

confirmed by Serong in his letter. The date of Australia’s official

involvement in Vietnam however, remains the same.

A prudent assessment made by Synott regarding the conditions he

faced before ordering that an advanced state of defensive measures

be adopted when entering the Long Tao shipping channel, had

obviously not been considered when the relevant authorities

allocated starting dates for the ‘official’ commencement of

Australia’s involvement in Vietnam. It would also be safe to assume

that the government of the day placed more diplomatic and political

value on the deployment of 30 non-combatant Army advisors to South

Vietnam, seeing them as an example of their support to a beleaguered

SVN government - and their US supporters. They were much more

visible than the arrival of two warships, purportedly on a port

visit to Saigon six and a half months previously, that were also

there to discretely ascertain the viability of

Sydney using the port

later, to support the further involvement of Australian forces in

the rapidly developing war.

It was into this rather inhospitable area that

Sydney and her escort

ventured repeatedly from June 1965 until November 1972, where they

were always assigned to the northern end of the Vung Tau anchorage.

These anchorage points were adjacent to Point Gahn Rai light, well

within mortar and rocket range of Long Son Island, Can Gio on the

Long Thahn Peninsula, and other places of opportunity within

striking distance of the Vung Tau anchorage, from where communist

forces could attack ships without warning.

[i]

Frank Uhlig Jr., ‘Fighting Where the Ground Was a Little

Damp: The War on the Coast and in the Rivers’, in, Frank

Uhlig Jr. Vietnam The

Naval Story, (Maryland: Naval Institute, 1986), p. 270.

[ii]

Texas Tech University (TTU), Vietnam Virtual Archive, Long

Tao Shipping Channel, RSSZ, Map Series 1501.

[iii]

Peter Edwards & Gregory Pemberton,

Crises and

Commitments: (Sydney: Allen &

Unwin,

1992), p. 243. Alastair Cooper, in David Stevens (Ed.),

The Royal Australian

Navy: The Australian Centenary of

Defence,

Vol. 3, (Melbourne: Oxford, Melbourne, 2001, p. 203.

[iv]

Jeffrey Grey, Up Top:

The Royal Australian Navy & South East Asian Conflicts

1955-1973, (Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1998), pp. 72-74.

[v]

Victor Croizat, The

Brown Water Navy: The River & Coastal War in Indo-China &

Vietnam, 1948-1972, (Dorset:

Blandford Press, 1984), p. 31.

[vi]

Letter from Admiral Sir Anthony M Synott, via Roger deLisle,

24 April 1993.

[vii]

Letter from Rear Admiral Peter H Doyle, via Roger deLisle,

20 May 1994.

[viii]

Lt. Cdr. Peter Maxwell Cumming RAN O263.

[ix]

‘Visit to the Republic of South Vietnam 14 Dec. 1962-14 Jan.

1963’, Report by Lt. Cdr. P M Cumming RAN, 14 Jan. 1963,

addressed to Flag Officer Commanding Australian Fleet, Flag

Officer Commanding Far East Fleet, CO HMAS

Quiberon,

Australian Defence Attaché Saigon.

[x]

Ibid

[xi]

Ibid

[xii]

Ibid

[xiii]

Ibid

[xiv]

Ibid

[xv]

Ibid

[xvi]

Temporary Brigadier Leslie

Irvine Hopton is recorded on the Nominal Roll of Vietnam

Veterans as having 748 days’ service as the Australian

Service Attaché, Saigon, from 01-01-1961 to 18-01-1963. And

yet Australia’s date of official involvement in the Vietnam

War is not until 31 July 1962. While Cumming served within

the officially designated involvement times, his name and

service details are not recorded on the Nominal Roll.

[xvii]

HMAS Quiberon,

Log Book, SP 866/1, Bundle 922, January 1963, NAA. HMAS

Queenborough, Log

Book, SP 866/1, Bundle 921, January 1963, NAA.

[xviii]

Report of Proceedings, HMAS

Quiberon, AWM 78

299/5, January 1963.

[xix]

Letter from Cdr Frank R Woods, via Roger deLisle, 24 June

1994.

[xx]

Ian McNeill, To Long

Tan: The Australian Army & the Vietnam War 1950-1966,

(Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1993), p. 42

[xxi]

Letter from Brigadier Francis P (Ted) Serong, via Roger

deLisle, 17 February 1999.

[xxii]

HMAS Vampire Log

Book, SP 805/1, Bundle 901, January 1962, NAA. The two ships

assumed Condition Yankee from 0305 to 0848, 25 January 1962,

and from 0815 to 1245, 29 January 1962. Condition Yankee is

only assumed in peacetime in dangerous circumstances e.g.,

fog or mines.